Arts

You are here

Howard Zinn: the biography of the people’s historian

October 5, 2012

Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left, By Martin Duberman

Reviewed by Libby Fung

Howard Zinn—historian, activist, and author ofA People’s History of the United States—gets a bit of his own treatment in this biography by Martin Duberman.

Born in 1922 in Brooklyn to a working-class, immigrant family, Zinn grew up with a sense of class consciousness, seeing his parents work so hard and have so little to show for it. A voracious reader, Zinn came across the works of Karl Marx while recuperating in a body cast after a part-time job as a caddy injured his hip.

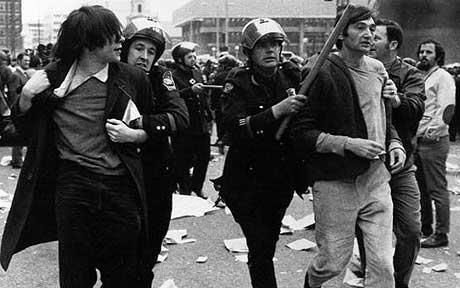

Zinn started his life of activism at the age of 17, leafleting local laundry workers to encourage them to join a union. His transition from liberal to radical came later that year, when some friends convinced Zinn to join them in a demonstration in Times Square. Mounted police broke up the nonviolent protest, and knocked Zinn unconscious. The incident changed Zinn’s outlook drastically, convincing him that there was something inherently wrong with the system, the government was not on the side of the people, and the “freedom of speech” touted by the American Dream was, in reality, not so free.

At the age of 18, Zinn became a shipyard worker and later enlisted in the air force, flying bomber missions during World War II. These experiences helped shape his views on war, producing one of the overarching questions in Zinn’s life—whether there was such a thing as a “just” or “justified” war. When is violence justified?

After the war, Zinn went to college under the GI bill and earned a PhD in history from Columbia. He then went to teach at Spelman College Atlanta, Georgia, one of the most prominent and respected schools at the time for black women. This was at the time of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which had deemed segregation to be unconstitutional, though little change had yet been made. Zinn brought his activism to the classroom, organizing his students to begin a campaign to abolish segregation in the Atlanta library system, in which they were ultimately successful. He also played roles in several sit-in demonstrations, either participating in the demonstration itself or acting as a liaison to the press. Zinn served as a senior advisor to the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC), organizing Freedom Schools and helping out in the voter registration at the height of tensions.

When the Vietnam War began, Zinn found his focus shifting from the civil rights movement towards the protests against the war, though he saw the two as mutually supporting issues. Zinn was one of two men who went to Hanoi to facilitate the release of three captured American pilots in the midst of the Tet Offensive. He was one of five American professors who were flown to Paris to participate in peace talks between North Vietnam and the US.

For what Zinn is most well-known for, there is surprisingly little written about his time writing A People’s History of the United States—a presentation of American history from the eyes of the common people. Duberman makes note of how, while the initial press run of the book was released to mixed reviews, mentions in popular culture—in the movie Good Will Hunting, in an episode of The Simpsons and an episode of The Sopranos—catapulted sales of the books to unheard of levels, selling over 2 million copies.

As a biography, Duberman takes a fairly thorough look into Zinn’s life, despite the fact that Zinn attempted to obscure his personal history by destroying nearly everything in his personal archives. In his writings, and even in this own autobiography (You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train), Zinn often neglected the personal aspects of life. Duberman has the unenviable task of attempting to fill in those holes, and to balance the two halves of Zinn’s life.

Duberman attempts to provide a context to the times that Zinn lived through, though that sometimes meant extended historical tangents. This book gives a good insight into Howard Zinn, giving context to the author of a seminal work that has since inspired millions of people.

Section:

- Log in to post comments