Arts

You are here

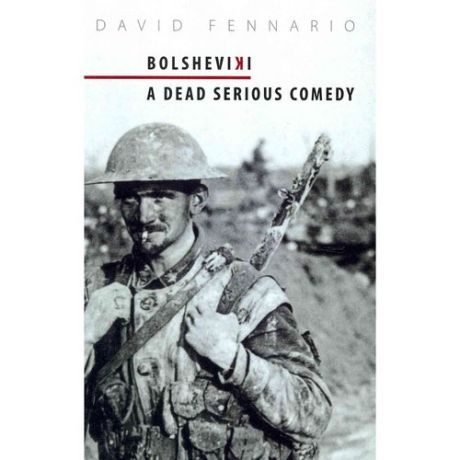

Bolsheviki: a play about war and revolution

August 5, 2013

Bolsheviki, the latest piece of theatre from Montreal playwright David Fennario, tells the story of Harry "Rosie" Rollins, a veteran of the First World War and native of Pointe St. Charles, the Montreal neighbourhood in which Fennario himself grew up. Rollins is a chatty, hard-drinking and hard-singing bilingual Irishman who is accosted by young reporter Jerry Nines one Remembrance Day. Rollins proceeds to give Nines, and by extension the audience, a lesson in the hidden history of the so-called "war to end all wars." Unlike what most us get in our high school history books, this is a history full of off-colour jokes, bawdy songs, insubordination, mutiny and revolution.

Rollins is the poor son of a single mother who grows up singing in taverns for spare change. He tells how, like many other Irish from the Pointe, he joined up as soon as the war started. Rosie's war is the not a war of genteel officers' clubs and discussions of strategy and private-schooled aristocrats shouting 'tally-ho', but rather a bewildering hellhole of constant shelling, trackless mud and ambitious officers who happily send the men to their deaths.

Rosie tells the young Nines of how he stuffed a sock in the mouth of a dying comrade in order to make him quiet down, how he dreamed of shooting his company commander in the back, and how he was befriended by Quebecois private 'Rummy' Robidou who introduces him to the idea of a soldiers' strike. Rummy is eventually shot by firing squad for refusing to undertake another suicide patrol.

Rosie tells Nines about how news of the Quebec anti-conscription riots in 1917 spread from bed to bed while he was in hospital recovering from wounds, and how a fracas started right in the hospital among the wounded, the first of the so-called "Wanna Go Home Riots"' Rosie tells of a war fought by working class kids on both sides, and how those working class kids came to realize that the real enemy was not the men on the other side of no man's land, but rather their own officers ordering them into battle.

Rosie takes this realisation back to Canada after the war, participating in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 and spending time in jail for being a revolutionary.

Those familiar with Fennario's work will recognise in Bolsheviki his ear for rough humour and the linguistic rhythms of the neighborhood in which he grew up, as well as his clear call for solidarity among working people. Nobody writes bilingual slang better than Fennario, and the show paints a vivid portrait of a man radicalised by war who tries to do something about it.The show's great strength is it's demonstration of the reality of revolution, that the movements that are capable of changing the world are not conjured up by "great men" but rather are formed by hundreds of thousands of ordinary people who decide they've had enough, ordinary people with dirt under their fingernails, who swear and brawl and like a drink.

The show is above all an acknowledgement and celebration of the potential power ordinary people have to change the world.

Bolsheviki was first produced in Montreal in late-2010. It's not currently being produced anywhere, but pick up a copy of the published script if you can, or pester a theatre in your city to produce it. It's a fitting salute, in Fennario's words, to "all those Bolsheviki that didn’t make it into the history books."

Section:

Topics: