News

You are here

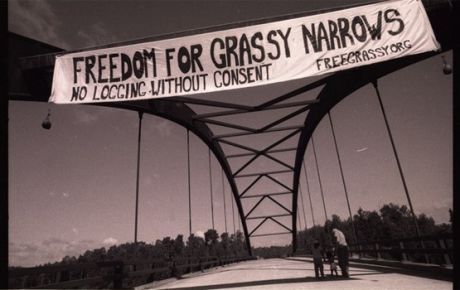

Grassy Narrows: one First Nation, two big battles

August 6, 2014

Grassy Narrows First Nation is in a decades-long fight to seek redress for the damages caused by the careless dumping of mercury by a paper company in the Wabigoon/English River system between 1962 and 1970. The other fight by the Nation is to bring about the end of clear-cut logging, a practice that only further damages the river system.

The fight has taken the form of a lengthy court battle against the province of Ontario for allowing a pulp mill company to clear-cut areas on traditional lands (so-called “Crown” lands) in 1997. The lawsuit was initiated in 2005, and, arguing its Treaty 3 harvesting rights, the Nation initially won its case in 2011. Unfortunately, the lower court’s decision was overturned by the Ontario Court of Appeal and on July 11, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruled unanimously against Grassy Narrows.

Supreme Court decision

The Nation had been arguing that the provincial government did not have jurisdiction because the Treaty was signed with the federal government. But SCC ruled “It is true that Treaty 3 was negotiated with the Crown in right of Canada. But that does not mean that the Crown in right of Ontario is not bound by and empowered to act with respect to the treaty…. Ontario has the power to take up lands … under Treaty 3, without federal approval or supervision.”

Needless to say, this case was followed closely by various levels of government. Several First Nations supported Grassy Narrows and were interveners at court hearings. On the other side, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, to their shame, supported Ontario.

Not only is the ruling hugely unjust for Grassy Narrows, but came as a setback coming so soon after the victory of the Tsilhqot'in decision, which recognized land title in non-treaty areas. Indigenous commentator Hayden King (who is also director of the Centre of Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University) pointed out that the pattern of breaking age-old treaty agreements is repeated in the SCC decision.

He argues that, firstly, the Court says the province has jurisdiction over lands, whereas First Nations see the provinces as “junior partners” in the treaty relationship. It seems the only obligation is for First Nations to be consulted, accommodated for any adverse results from breaking the treaty, and for harm to First Nations to be minimized.

King also points out that the SCC decision relied on the treaty and follow-up federal and provincial laws, with no consideration on the perspectives of the people of Grassy Narrows. His conclusion: according to the decision, First Nations have no place in Confederation. “For provinces governed by the Numbered Treaties, the ruling means business as usual: consult, infringe, accommodate… In the eyes of the Court, treaties and the accompanying extinguishment of title are a dead end for First Nations.”

But faced with mercury poisoning, clear-cut logging, floods caused by the creation of hydro-electric dams, Grassy Narrows has the support of numerous First Nations as well as non-Indigenous allies. The struggle continues. No justice, no peace.

For more information visit FreeGrassy.net

Section: