Features

You are here

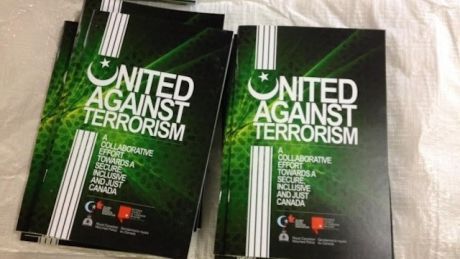

“United Against Terrorism” handbook exposes Islamophobia

October 8, 2014

On September 29, a group of Canadian Islamic associations, including the Islamic Social Services Association and the National Council of Canadian Muslims, released a handbook entitled “United Against Terrorism: A Collaborative Effort Towards a Secure, Inclusive and Just Canada.” It was an effort to urge law enforcement agencies and the media to stop using terms that link Islam as a religion with terrorism.

The handbook identifies a number of phrases that should be discontinued when talking about terrorism:

-Moderate Muslim: “This term is meant to divide and classify Muslims based on Islamophobic jargon.”

-Jihad: “An Arabic term meaning striving, struggling and exertion in the path of good… Jihad is not holy war either. Islam allows for Jihad in the form of a military action in self-defence only.”

-Islamist terrorism or Islamic extremism: “Do not conflate religiosity with radicalization or conflate religious devotion with a propensity to commit acts of violence.”

RCMP hypocrisy

The RCMP is listed as a contributor to the handbook, and one might think they would welcome such a publication calling for unity and cooperation with the Canadian state against terrorism—which Canada’s Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird recently described as “the greatest challenge of our generation.”

But after months of attempted collaboration the police force pulled its support on the very day the handbook was released at a media conference, with no prior warning. That same evening RCMP headquarters issued a statement saying: “The RCMP hasn’t issued any guidance or guidelines to other departments, nor has it agreed not to use terms such as ‘Islamist terrorism,’ ‘Islamic extremism’ or ‘jihad’.” They also stated that parts of the booklet have an "adversarial tone.”

This is shameful, though not surprising, given the renewed drive to war against Iraq and Syria that was gearing up at precisely the same time, four days prior to Harper’s commitment in the House of Commons to air strikes. The handbook’s release has exposed the unwillingness of both law enforcement and the media to stop using misleading and Islamophobic terms and phrases, and their complicity in drumming up public support for a new war—abroad and at home.

War at home

It is unacceptable that once again the Canadian-Muslim community has had to publicly demonstrate its willingness to counter the supposed threat of terror in its midst in order to earn the credibility to decry Islamophobia. The emergence of ISIS and its international connections, in particular the much-publicized beheadings by internationals, has heightened the “blame-game” at home, and this has given rise to a debate within the Muslim community over the extent to which it must now alleviate new fears.

The Canadian Council of Imams (CCI), the National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM), and the Muslim Council of Greater Hamilton (MCGH) have all released statements condemning ISIS and any forms of extremism and violence. Muslim Students’ Associations on university campuses are holding events against ISIS’s actions. There is wide debate on Twitter at both #NotinMyName and its parody, #MuslimApologies.

While acts of indiscriminate violence committed anywhere are to be condemned, media and law enforcement are using “home-grown” terror and the exaggeration of its actual threat, as a means to boost public support for Western imperialism. And while it is perfectly understandable why some in the Muslim community feel the pressure to do so, joining that chorus should not have to be a necessary precondition to challenge the equation of Islam with terror.

Strategy

“United Against Terrorism” is an important refutation of the public discourse that feeds Islamophobia. But it is also a victim of that discourse.

The handbook rightly encourages youth with legitimate frustrations over Western intervention to get involved in political lobbying and civic engagement instead of travelling abroad to fight in those conflicts directly. And while the handbook encourages members of the Muslim community to alert elders so they can take action against those with extremist views, it also states that co-operation with CSIS and the RCMP in investigations is voluntary and there is no obligation to answer questions.

While the main thrust of the handbook is aimed at countering Islamophobia in law enforcement, it also cooperated with the RCMP in targeting youth who may be frustrated about foreign conflicts and potentially drawn to terrorist strategies or extremist groups. The purpose of this dual target is, in the words of Shahina Siddiqui, president of the Islamic Social Services Association, to “disseminate an accurate and responsible anti-violence civic narrative.”

The RCMP’s rejection of the handbook shows they are more interested in stoking Islamophobia than in challenging terrorism, and that the state is not an ally in the struggle for peace and justice. Helping the police target racialized youth only encourages more Islamophobia.

If the Canadian state cared about terrorism it would stop fueling ISIS by bombing Iraq, stop supporting counter-revolution by arming Saudi Arabia, and stop its own terrorist policies of colonialism and imperialism. Groups like ISIS are a response to the terror of Western imperialism, like the Iraq War that killed a million people and Western intervention that armed sectarian groups in Syria. The best way to fight terrorism is to build unity against war and Islamophobia, and support revolutionary movements that offer an alternative to ISIS. That is the kind of unity that can undercut any potential false attraction to regressive politics that were fostered by Western intervention in the first place.

Section:

Topics: