Arts

You are here

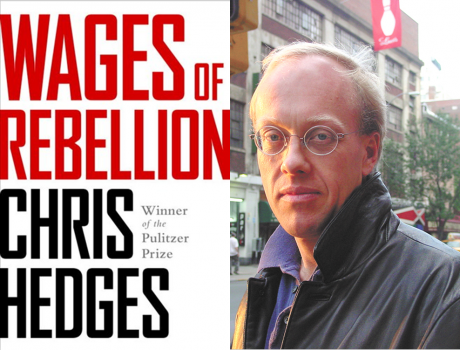

Wages of despair

June 5, 2015

Prominent journalist Chris Hedges’ new book, Wages of Rebellion, is another scathing critique of capitalism—and the repression it doles out against the inevitable uprisings it produces. But by focusing on heroic individuals and downplaying the movements from which they emerge, Hedges reinforces an elitist vision of change.

Rebels

Hedges worked as a foreign correspondent to the New York Times for 15 years, until he opposed the 2003 Iraq War. Since then he has turned his critique against the establishment and supported movements like Occupy. It’s refreshing to read mainstream writers who use their wide following to denounce the system and support resistance.

“We live in a revolutionary moment,” Hedges begins, after quoting Marx. While the mainstream press was preoccupied with the role of social media during the Arab Spring and Occupy movements of a few years ago, Hedges makes a clear case that these and other revolts are the product of the economic and ecologic contradictions of capitalism—where the system has no means of reform and increasing means of repression:

“The refusal by the corporate state to address even the minimal grievances of the citizenry, its abject failure to remedy the mounting state repression, the chronic unemployment and underemployment and the massive debt peonage that is crippling millions of Americans, and the widespread despair and loss of hope, along with the collapse of institutions meant to carry piecemeal and incremental reform, including the courts, make blowback inevitable.”

In his latest book, Hedges focuses on the “wages,” or compensation, that the state awards to rebels—including house arrest for Julian Assange and jail for Chelsea Manning for leaking war crimes, exile for Edward Snowden for exposing government surveillance, a life in jail for Mumia Abu Jamal for being part of the Black Panthers, and assassination for Martin Luther King.

As Hedges sums up his book: “Exploring the forces and personalities that foster rebellion, it looks at the personal cost of rebellion—what it takes emotionally, psychologically, and physically to defy absolute power…The persecution of these rebels is the harbinger of what is to come: the rise of a bitter world where criminals in tailored suits and gangsters in beribboned military uniforms—proposed up by a vast internal and external security apparatus, a compliant press, and a morally bankrupt political elite—hunt down and cage all who resist.”

Nostalgia and catastrophism

For Hedges, this is all new. Like many prominent left authors, like Naomi Klein, Hedges does not oppose capitalism per se but the supposedly new version of capitalism. Throughout Wages of Revolt Hedges refers to “corporate capitalism” and “structures of power that have surrendered to corporate control,” of “corrupt governments,” a “compliant media,” and an “ineffectual liberal elite”—as if there were some earlier version of capitalism that had a neutral state subject to democratic control, informed by objective media and ruled by benevolent elites.

As a result Hedges combines nostalgia for the past with a catastrophism about the present—that we now have a “totalitarian” and “omnipotent” state that makes resistance nearly impossible: “All calls for revolt, for halting the march toward economic, political, and environmental catastrophe, are ignored or ridiculed…We bow slavishly before the enticing illusion provided to us by our masters of limitless power, wealth, and technological prowess…We lack the emotional and intellectual creativity to shut down the engine of global capitalism…The public’s inability to grasp the pathology of our oligarchic corporate elite makes it difficult to organize effective resistance.”

Elitism

By seeing neoliberalism as an ideological aberrancy imposed on capitalism, and which has obliterated opposition, Hedges’ view of resistance retreats to the ideological plane: “Once we discover new words and ideas through which to perceive and explain reality, we free ourselves from neoliberalism, which functions…like a state religion.” He calls for a “radical shift in consciousness,” but where this will come from if the state is indeed omnipotent and ordinary people supposedly unable to resist?

It’s frustrating that a book with “rebellion” in the title spends so little time discussing actual rebellions. There are multiple passing references (from the French Revolution to the Arab Spring and Occupy movement) but the vast majority of the book is about how powerful the state is in crushing rebellion—from surveillance to torture, and from vigilante violence to prisons. While Hedges mentions the killings of Mike Brown and Eric Garner, he says nothing about the Black Lives Matter rebellions or the historic strikes and protests for a $15 minimum wage.

Instead, he dismisses the “moribund labour movement,” and claims that “with the decimation of the US manufacturing base and the dismantling of our unions and opposition parties, we will have to search for different instruments of rebellion.” But with ordinary people apparently incapable of resisting the omnipotent state, Hedges looks to heroic individuals.

By focusing on persecuted individuals separated from the movements that gave rise to them, Hedges holds up a model that is elitist and moralizing, and almost glorifies persecution: “The person with moral courage defies the crowd, stands up as a solitary individual, shuns the intoxicating embrace of comradeship, and is disobedient to authority, even at the risk of his or her life, for a higher principle. And with moral courage comes persecution…The rebel, possessed of ‘sublime madness,’ speaks words that resonate only with those who can see through the façade. The rebel functions as a prophet” and “has few friends.”

Small scale rebellion or mass revolution

This is problematic when it comes to movement building, which Hedges doesn’t discuss at all. Last year he dismissed the historic People’s Climate March as “one of the last gasps of conventional liberalism’s response to the climate crisis” and counterposed it to the smaller “radical groups” engaging in direct actions. As he wrote at the time: “Resistance will mean severing ourselves from the dominant culture to build small, self-sustaining communities.”

Because Hedges believes the right-wing interpretation of the Russian Revolution, that an organized overthrow of capitalism will lead to tyranny, his solution to state power is to “carve out spaces” and build “autonomous” and “self-governing communities”—despite spending an entire book detailing how the state that will “hunt and cage” those who resist. Because he sees the working class as either non-existent or passive, there is no sense of how an alternative economy could emerge from those upon whose labour corporate profits depend. And because he counterposes the millions starting to question capitalism’s contradictions from the minority of self-identified radicals, he creates a false dichotomy between the fight for reform and the process of revolution.

Wages of Rebellion is a helpful warning of the extent the state will go to protect corporate power, and the need for a future without capitalism. But getting there will require more than praising heroic individuals and telling people how horrible capitalism is, it will require rebels linking the existing movements for reform with a future revolutionary transformation.

Section: