Features

You are here

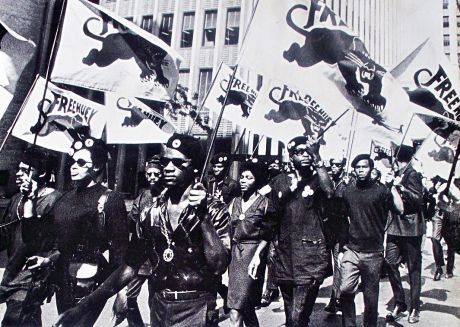

50 years since the Black Panther Party

April 13, 2016

Fifty years ago, in West Oakland, two college classmates took action against the poverty, inequality and police brutality that they witnessed all around them. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, on October 15, 1966 created the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP).

They were inspired by Malcolm X’s writings on self defense and sought to create an organization that melded the militancy of the Nation of Islam with the broader goals of the Civil Rights Movement.

Origins and growth

The party started off modestly—Newton, Seale and a few recruits went out on patrols, armed with shotguns, trying to stop police from harassing black people in their neighbourhoods.

In the volatile atmosphere of 1960s America, where racism, riots and resistance were rampant, the BPP grew quickly. The BPP gathered new members and sympathizers based on their community organizing ameliorate the conditions suffered by those struggling around them and their political visions that saw Black self-organization and socialism as the antidotes to the oppression and exploitation of the Black community.

The party really began to take off when Newton was arrested for killing a police officer and the party launched an incredibly bold and popular campaign to free him. Their work continued to grow during this period as the Oakland BPP opened community food banks, health care clinics, and campaigned hard on their 10 point program which emphasized housing, health care, and an end to war, exploitation and police violence.

Politics

While the BPP was a staunchly black nationalist organization, it differed from other such organizations in its internationalist and anti-capitalist approach to black liberation. Contrary to the notions of black capitalism, a return to Africa or cultural identity-based strategies, the difference between the BPP and other organizations at the time is explained best by this quote from leading BPP member, Bobby Hutton:

“We’re nationalists, because we see ourselves as a nation within a nation. But we’re revolutionary nationalists. We don’t see ourselves as a national unit for racist reasons but as a necessity for us to progress as human beings and live on the face of this earth. We don’t fight racism with racism. We fight racism with solidarity. We don’t fight exploitative capitalism with black capitalism. We fight capitalism with revolutionary socialism.”

This revolutionary approach was heavily influenced by Marxism and the writings of Lenin and Mao. The founding members of the BPP saw the material basis for oppression and recognized the need for solidarity in the fight against the white supremacist capitalist machine that left their communities without decent housing, education, jobs or medical care and occupied by vicious police.

Memorably, Huey P. Newton stood up to homophobia and sexism within the Civil Rights Movement in a speech in 1970: “Whatever your personal opinions and your insecurities about homosexuality and the various liberation movements among homosexuals and women (and I speak of the homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should try to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion….When we have revolutionary conferences, rallies, and demonstrations,there should be full participation of the gay liberation movement and the women’s liberation movement.”

The BPP was leading the argument in activist circles that radicals of all races, religions, sexual orientations and genders had to come together to fight oppression and exploitation. Through their newspaper, The Black Panther, they organized thousands of people into political activity. A paper sale would be the most exciting thing some of the neighbourhoods they sold in had ever seen, and became a way for the party to grow beyond the confines of West Oakland. The Black Panther had a readership of 250,000 at its peak and the BPP could claim 10,000 members in 1969.

Decline

However, in many ways the BPP would come to be undermined by their own success. As they grew quickly in the revolutionary atmosphere of the 1960s, branches began to pop up all over the country that did not have the same vision as the Oakland founders.

Many chapters committed crimes and allowed sexism to continue within their organizations, things that were anathema to the foundation of the BPP. The BPP organized based on neighbourhoods and campaigns and, while many of their members and sympathizers were working class, the party’s activity never drew on the strength of the organized working class or their workplaces. The corrective influence of the working class was absent in the BPP’s activity and, thus, failed to influence the path of the party towards strikes and industrial activity. Charismatic and confident leaders could right the party in times of trouble, but a lack of organizational memory and democratic tradition meant that it was hard for the rank-and-file of the party to argue against those charismatic leaders and correct them when they made wrong turns.

In addition, the fast paced recruitment and pace of activity allowed the scores of FBI spies and provocateurs (backed by millions in government-funding) to infiltrate and undermine the work of the BPP.The determined campaign of the US government to undermine, sabotage and drown in blood the BPP led to its collapse. In the first few months of 1971 the party began to come apart. A wing devoted to armed uprising against the police and the state immediately was expelled from the party and the remainder backed off from the politics of armed self-defence, and revolutionary politics instead turning to elections. By 1972 the party’s membership and influence were dwindling and the leadership put all of their resources into the 1973 election for Mayor of Oakland which they lost in a run off election. The party continued to have some influence in electoral politics in California, but never regained the position of leadership it once had.

Legacy

The BPP faced an incredible challenge, trying to grow into an organization that could lead a movement against capitalism, imperialism and racism, against a state set on destroying them. Fifty years later, their 10-point program stands as a set of ideas and concrete demands that would eliminate racism and challenge the capitalist system to its very core. The echoes of this program and the Panthers’ legacy can be heard in the demands of Occupy Wall Street, the chants of Black Lives Matter protestors and the aspirations of Bernie Sanders supporters across America:

1. We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

2. We want full employment for our people.

3. We want an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our black and oppressed communities.

4. We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

5. We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

6. We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

7. We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

8. We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

9. We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

Join the conference Ideas for Real Change: Marxism 2016, including the discussion “50 years since the Black Panthers” with Norman Otis Richmond, prominent Black activist in Toronto and former member of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit, and socialist activist Ali Awali. Register today and join/share on facebook.

Section: