Arts

You are here

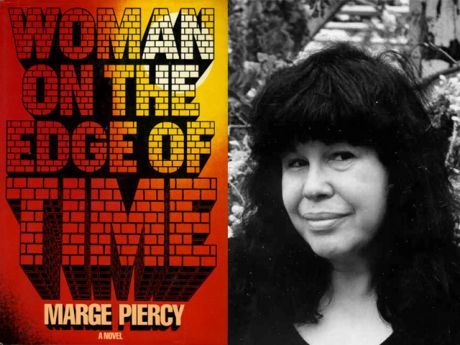

Woman on the Edge of Time, 40 years later

June 13, 2016

This year 2016 is the 40th anniversary of the publication of Woman on the Edge of Time, a futuristic novel written by American feminist and socialist, Marge Piercy. It’s fitting that the book should be republished this year with a new introduction by Piercy, who has just turned 80 this March, because it is the utopia we need in these most dystopian of times.

In many ways, as Piercy elucidates in her introduction, things have gotten much worse for the vast majority of Americans (and for most of the rest of us as well) since the publication of her novel:

“Woman on the Edge of Time was first published forty years ago and begun three and a half years before that. The early 1970s was a time of great political ferment and optimism among those of us who longed for change, for a more just and egalitarian society with more opportunities for all the people, not just some of them.

Since then inequality has greatly increased. As I write this, more people are poor, more people are working two or three jobs just to get by, more people find that their savings and their future have been wiped out by bad health or by losing their jobs. The homeless are everywhere, not just the single man or woman down on their luck or the shuffling bag lady but whole families with their children.

There is less opportunity for the children of ordinary people to afford college; if they can go, they will be dragging huge debt through much of their adult lives […] At the time I wrote this novel, women were making huge gains in control of their bodies and their lives. Not only has that momentum been lost, but many of the rights we worked so hard to secure are being taken from us by Congress and state legislatures every year.

But we must also understand that the attempt to take away a woman’s control over her body is part of a larger attempt to take away any real control over the lives of most of the population. Now, corporations and the very wealthy 1 percent control elections. Now, the media are propaganda machines and the only investigative reporting is on Comedy Central, HBO or the Web.”

Racism, sexism and mad oppression

The protagonist in Woman on the Edge of Time is a 37 year old Chicana woman living in Manhattan, Consuelo/Connie Ramos. When we meet her at the beginning of the novel she’s at one of the very low points in her life. She is living on welfare and barely eking out an existence. She carries with her the shame of having had her young daughter taken from her by social services because of a period of deep depression she went through when her Black lover Claud, a blind man eking out a living as a petty criminal, died in prison.

In addition to dealing with questions of racism and women’s oppression, and how much these twin evils weigh most on those living in poverty, Woman on the Edge of Time is also an exploration of the way mental institutions were (and continue to be) a dumping ground for the poor, the rebels, those who don’t fit in.

Piercy went inside mental institutions at the time in preparation for writing her novel:

“I was brought in undercover by people who worked in the mental institutions of the time so I could experience conditions inside. People risked their jobs to help me. Now mental patients are dumped on the streets without support. We still drug but we provide little counseling or safe and comfortable lodging. It’s no improvement.”

Connie, who was previously held against her will at Bellevue during her depression, finds herself there again when she tries to defend her pregnant niece Dolly who has been beaten up by her boyfriend and pimp, Geraldo.

No one listens to her story of having been beaten by Geraldo while attempting to defend her niece. They take his word for it that she attacked him, and since Connie’s already been institutionalized once before, she has several strikes against her – crazy, Mexican-American, a woman and poor.

Piercy’s book is a masterful look at the way those on the bottom of society are treated by those with power—whether it be judges, social workers, doctors. But it’s also a hopeful novel because of the utopian aspect.

Utopian

Connie begins to experience visits from a person whose name is Luciente, who eventually tells her they are a person from the future: “I’m from a village in Massachusetts—Mattapoisett. Only I live there in 2137.”

Connie thinks at first these visits must be some kind of strange wish fulfillment since Luciente seems to be a good-looking young Latino/indigenous male. The first time Connie time-travels to Mattapoisett she discovers that Luciente is indeed female but doesn’t present as females often do in Connie’s time: weak, deferential, “feminine.”

This is one of the differences Connie slowly discovers on subsequent visits to Mattapoisett—that gender roles have undergone a sea change and that there are no longer traits that are seen as being essentially “male” or “female.”

She is at first dismayed to discover that life in Mattapoisett reminds her of her own heritage—people living in poverty off the land in Texas, after they moved north from Mexico: “Goats! Jesus y Maria, this place is like my Tio Manuel’s in Texas. A bunch of wetback refugees! Goats, chickens running around, a lot of huts scavenged out of real houses and the white folks’ garbage. All that lacks is a couple of old cars on blocks in the yard!”

But throughout the course of the novel Connie comes to understand the people of Mattapoisett and their way of life. It’s not a refusal of technology—their society is in many ways much more technologically advanced than the present she is living in—but it’s about the use of technology in order to benefit people and the planet, rather than the profits of a few which risk destroying all life, human and otherwise.

Connie is also initially shocked at the way children are born and cared for. They are born not of woman but develop in a brooder where genetic material is stored. Each child has three “coms” or comothers (who maybe be male or female). Luciente explains why: “It was part of women’s long revolution. When we were breaking all the old hierarchies. Cause as long as we were biologically enchained, we’d never be equal. And males would never be humanized to be loving and tender. So we all became mothers. Every child has three. To break the nuclear bonding.”

But by the end of the novel Connie has come to the understanding that her daughter Angelina would have a much better chance of surviving and growing up strong and happy in this strange new world:

“Yes, you can have my child, you can keep my child. She will be strong there, well fed, well housed, well taught, she will grow up much better and stronger and smarter than I. I assent, I give you my battered body as recompense and my rotten heart. Take her, keep her! She will walk in strength like a man and never sell her body and she will nurse her babies like a woman and live in love like a garden, like that children’s house of many colors. People of the rainbow with its end fixed in earth, I give her to you!”

Part of the poignancy of the novel is the contrast between the harsh reality Connie lives in and the possibilities she glimpses in her visits to Mattapoisett. However, it’s also clear that this future is not a forgone conclusion. The existence or non-existence of Mattapoisett depends on the decisions that Connie and others make in her time.

Build the future

This is brought home to Connie when she accidentally finds herself in another possible future where gender roles have become more rigid, where women are essentially slaves, and where the vast majority of people (unless they are the privileged wealthy) live never seeing the outside world, which has become horribly polluted and uninhabitable.

“So that was the other world that might come to be. That was Luciente’s war, and she (Connie) was enlisted in it.”

Connie comes to understand that in spite of the wonderful things she has seen in the new society they cannot be taken for granted. Luciente and her fellow citizens regularly volunteer for defence missions because the rulers in the old society have not given up in their attempts to crush revolution.

As Luciente warns Connie at one point, “Those of your time who fought hard for change, often they had myths that a revolution was inevitable. But nothing is! All things interlock. We are only one possible future. Do you grasp?”

The point of Woman on the Edge of Time is not, of course, to be a blueprint for the future society. As Piercy stresses, writing utopian fiction is not about foretelling the future:

“Why write a novel like Woman on the Edge of Time set in the future? The point of writing about the future is not to predict it; I’m not pretending to be Nostradamus. The point of such writing is to influence the present by extrapolating current trends for advancement or detriment. …The point of creating futures is to get people to imagine what they want and don’t want to happen down the road and maybe do something about it.”

If we think about Piercy’s novel today it may seem like it is just that—a utopia, which can never exist in the real world. As Piercy admits in her introduction things have gotten so much worse in the real world since the book was first published.

The environmental degradation that Piercy alludes to has continued apace. Climate change is a reality and is threatening the continued existence of human life on the planet. The gap between the 1% and the rest of us has widened immeasurably. Racism, women’s oppression, the shunting of the poor, LGBTQ and racialized communities into institutions, whether prisons or mental institutions, is very much with us.

But the hope lies, as ever, in people’s ability to organize collectively to overturn a system that makes no human sense. That is why movements like Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Idle no More have sprung up. That is why millions flocked to Bernie Sanders’ rallies in the US.

It is the hope that the continuing status quo represented by Hillary Clinton—a status quo that means more bloody war and death in places like Iraq and Syria, creating millions of refugees, the continued erosion of rights and income for working class people or, on the other hand, the racist scapegoating by Donald Trump—the hope that these are not the only alternatives on offer.

This is why someone who calls himself a democratic socialist, although he is still tied to the ruling class Democratic Party, galvanized people across the US to believe in another future. Ultimately that other future will depend not on Bernie Sanders himself, but on the actions of the millions who are supporting him and on whether they can build a sustained movement to really challenge the system that underpins the dystopia we are moving towards.

So, if you’ve never read Piercy’s novel there’s no better time than now to be galvanized and moved into action by the politics of hope.

Section: