Features

You are here

Treaty Alliance, tar sands resistance and settler solidarity

September 29, 2016

An historic advance in the struggle to stop expansion of the Alberta Tar Sands has taken place with the signing of The Treaty Alliance Against Tar Sands Expansion.

After years of waging separate struggles to stop individual pipeline projects the climate justice movement in North America has finally been united through the leadership of First Nations and Indigenous Tribes to form a wall of opposition that will prevent any further expansion of the Alberta Tar Sands.

This treaty also presents a challenge to climate justice activists in settler-colonial society to stand in solidarity to preserve, build on and strengthen this united movement. We must now rise to the level of First Nations by overcoming divisions within our own communities and connecting the fight against climate change to the struggle for social and economic justice and embracing the fight for a green economy.

Treaty Alliance

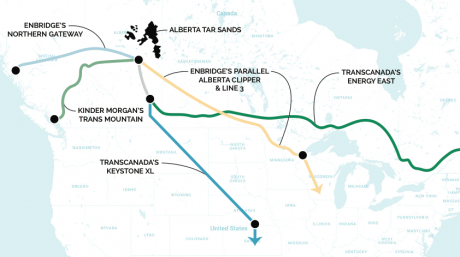

On Thursday, September 22 more than 50 First Nations and Tribes from across Canada and the Northern US gathered together on Musqueam Territory in Vancouver and Mowhawk Territory in Montreal to sign a continent-wide Indigenous Treaty: The Treaty Alliance Against Tar Sands Expansion. The treaty commits signatories to working together to stop all proposed tar sands pipeline, tanker and rail projects in their respective territorial lands and waters including Kinder Morgan, Energy East, Line 3, Northern Gateway and Keystone XL. As the Treaty explains, “Tar Sands expansion is a collective threat to our Nations. It requires a collective response. Therefore, our Nations hereby join together under the present treaty to officially prohibit and to agree to collectively challenge and resist the use of our respective territories and coasts in connection with the expansion of the production of the Alberta Tar Sands, including for the transport of such expanded production, whether by pipeline, rail or tanker.”

Led by the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, under the leadership of Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, the treaty follows on the remarkable unity achieved in the Yinka Dene Alliance’s Fraser Declaration which united nations along the route of Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline to successfully oppose the project.

“The Yinka Dene have already shown in the case of Enbridge’s Northern Gateway that a pipeline cannot hope to pass through a unified wall of Indigenous opposition,” said Carrier Sekani Tribal Chief Terry Teegee. “You will now see the same thing play out with all other tar sands pipelines, including another failed BC pipeline – Kinder Morgan.”

“What this Treaty means is that from Quebec, we will work with our First Nation allies in BC to make sure that the Kinder Morgan pipeline does not pass and we will also work with our Tribal allies in Minnesota as they take on Enbridge’s Line 3 expansion, and we know they’ll help us do the same against Energy East,” said Kanesatake Grand Chief Serge Simon.

As he explained, the movement against tar sands expansion is for the expansion of alternatives: “Tar sands are, I think, a national shame. If it were up to me it would be shut down tomorrow. But it would cause a lot of pain for people in Alberta, so our alliance is going to promote, in the strongest possible terms, massive investment in Alberta in another type of economy. These two actions, they go hand in hand. We’re not proposing to destroy Alberta, we’re trying to help it, and we’re trying to help the country, and we’re trying to help this planet.”

Colonial response

The Federal Liberal government responded to the treaty the following day, refusing to address its content, and instead attacking the unity of First Nations. "If you put the mayors of major cities in British Columbia and Alberta in a room you'd probably not get consensus and you'd certainly not get unity. If you put the premiers in a room talking about these energy projects there would be a difference of opinion. So too, no doubt, there will be a difference of opinion in Indigenous communities," Natural Resources Minister, Jim Carr said in an interview with Chris Hall on The House. Carr argued further that there are other Indigenous communities "who have spotted opportunity" in natural resource development.

Carr’s statements continue a long history of divide and rule policy from Canada’s corporate elite. For hundreds of years they have used the Canadian state to fragment and isolate First Nations, undermine their traditional governance structures and cultures, destroy their languages and shatter their social cohesion in order to sever their ties to the land, air and water and open up their territories for profitable extractive development.

First Nations today are faced with a constant barrage of demands from regulatory agencies working hand in glove with the resource extraction industries; demands which they often do not have the funds to adequately assess or respond to. These captured regulators, backed by the state, perpetually seek to create an air of inevitability and forward momentum for these projects—forcing First Nations to choose between stoically defending their identity as a people, as defined by their connection to the land, air and water, or receiving desperately needed resources to rebuild communities devastated by hundreds of years of genocidal colonial policy.

Settler solidarity

In this context it is hardly surprising that some First Nations and First Nations’ Leaders have decided to support some of these projects. Many do so with a heavy heart, but feel they have a duty to bring badly needed jobs and resources to their communities. As members of settler-colonial society we have no right to criticize the decisions made by First Nations leaders and their communities. Genuine solidarity means fighting our own 1% and lifting the boot of the settler Canadian state off the backs of our First Nations sisters and brothers. This kind of solidarity from non-Indigenous climate activists and organizations can play a vital role in making it easier for First Nations to resist the immense pressure put on them by government, regulatory agencies and industry.

One of the most profound examples of this happened in the midst of the mass protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle in 1999. Poor nations were being railroaded by a trade negotiation process that was stacked against them into opening up their fragile economies to further exploitation by first world corporations. Inspired by the united protests of tens of thousands of social justice, environmental and labour activists, representatives of more than 40 of the poorest nations walked out en masse and joined protestors in the streets—permanently derailing the talks, sparking solidarity protests in dozens of countries and launching a mass anti-globalization movement that swept across the globe over the next two years.

Standing Rock

The Treaty Alliance also comes in the wake of the massive and inspiring blockade of the Dakota Access Pipeline led by the Standing Rock Sioux. Assembled in a relatively isolated location along the Missouri River in North Dakota, the camp has drawn thousands of activists from hundreds of First Nations and Tribes across Turtle Island, turning the camp into a small city. After weeks of escalating confrontations between non-violent land and water protectors, trying to stop the destruction of sacred burial sites, and racist police and security forces, the state governor called in the National Guard.

In that week hundreds of solidarity demonstrations were held in cities and towns across North America. An important report from Democracy Now anchor Amy Goodman recorded racist security goons using their attack dogs against unarmed women, men and children. It was picked up by major networks after weeks of a virtual media blackout, exposing for millions of Americans what was going on. It was in the face of this solidarity that president Obama felt forced to intervene to stop construction on some sections and Army Corp of Engineers refused to cooperate with the project. The fight to stop DAPL is not over but this victory demonstrates what is possible with solidarity.

We will need to continue to build on this inspiring example and to follow the leadership shown in the Treaty Alliance. However, it is not enough for non-Indigenous activists to applaud the leadership of UBCIC and First Nations or to approach solidarity from a purely moral position. For many in the movement the “justice” in climate justice is largely isolated to justice for First Nations but it should also mean justice for working class people in our own communities. This means our task is not simply to stand behind First Nations, supporting their protests, donating to their court cases and admiring their leadership. To limit our solidarity to this would be to hold First Nations up as a shield against pipelines, leaving them to carry the brunt of the struggle. We also can’t opportunistically “piggy back” on the unity of First Nations to build our own as one activist in Vancouver recently described it. A genuine decolonizing approach must learn from Indigenous leadership and apply those lessons to struggles we share in common in settler-colonial society. It means challenging the false division in settler-colonial society between taking action to stop climate change and addressing the social and economic crisis we face as a result of the climate crisis and the corporate drive for profit that is behind it.

First Nations activists have linked the fight to protect their territories to the fight to end violence against Indigenous women, to creating jobs, combating poverty, repairing and expanding public services and many more struggles for social and economic justice. They have also led the way in implementing renewable energy projects to reduce emissions and create green jobs.

As Grand Chief Derek Nepinak of The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs stated when signing the treaty, “The solutions to the climate crisis are at hand and some of our Nations have taken the lead in implementing them.” One inspiring example of this has been the Lubicon Solar project developed by the Lubicon Cree First Nation situated in territories devastated by the Tar Sands. These same struggles exist for millions of working class people in non-Indigenous communities from the fight for green jobs, to the struggle to raise the minimum wage to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Fight for jobs, justice and the climate

This week Tolko Industries announced the closure of its sawmill in Merritt, BC destroying 200 good union jobs, the largest employer in this small town. These workers and their community are direct victims of climate change. The company argues they were forced to close the mill due to a sharp reduction in the Annual Allowable Cut now that the accelerated cutting of forests killed by the Mountain Pine Beetle is coming to an end. More closures are expected in other mill towns. The Mountain Pine Beetle explosion which has destroyed millions of acres of Lodgepole Pine forest in BC’s interior is now spreading across Alberta and threatens to sweep across much of the northern boreal forests into Ontario and beyond. The Pine Beetle is a native species that was thrown out of its natural equilibrium with the trees it breeds in by a one degree increase in the average temperature in BC’s Interior.

The fight to save the mill is now on. This is a fight that the climate justice movement should support along with many others. In Vancouver, bus drivers are pushing to implement a transit plan that would create 4300 full time green jobs annually. Mill workers and environmentalists on Vancouver Island are fighting raw log exports which have fuelled clear cut logging, destroying vital carbon sinks, and starved local mills of timber. In Burnaby, 150 workers at the Chevron refinery are threatened with the loss of their jobs if Kinder Morgan’s pipeline is approved and raw bitumen export replaces local oil refining.

In 1999 it was the alliance of Teamsters and Turtles that inspired a global movement and gave poor nations the support they needed to resist the big imperial powers. Today it is the duty of the climate justice movement to rebuild this unity if we truly wish to be in solidarity with First Nations.

Section: