Arts

You are here

Tashme authors confront racism past, present

September 26, 2019

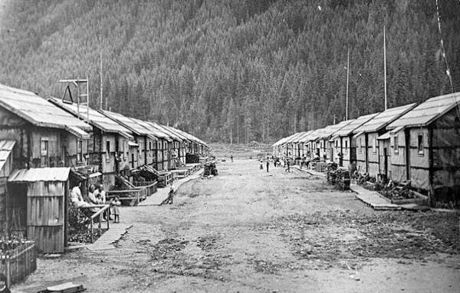

Actors and creators Julie Tamiko Manning and Matt Miwa, both half-Japanese-Canadian, third and fourth generation respectively, met while doing a play together and discovered their families shared a history: Tashme Internment Camp, one of several locations where Japanese-Canadians were interned during WW2.

The result of this encounter was The Tashme Project: A Living Archive, the product of 70 hours of recorded interviews of 25 people who had been interned from the age of 16 and below, converted into a 75-minute play.

In talk-backs after the show the creators revealed how hard it was to get even the Nisei, or second generation, to talk about their experiences in the camp as children. The Issei, or first generation, were already gone, and the creators suspect they would have been even more reluctant to speak of their experience given that they bore a much heavier burden of understanding the injustice.

But once the Nisei got into the interviews, they had a lot to say. On the cutting room floor (editing of the script) some got three full stories, some one line, and all interspersed with the creators’ interaction about the ethics of what they were doing: are we right to do these interviews and then leave, after stirring up all these memories? Are we right to bring up the issue of the $21,000 allocated by the federal government in the 80s for each of the 13,000 survivors long after those who deserved reparations most were gone?

Initially, the creators had not intended to create a piece of “verbatim theatre”, a theatre technique where actual words are used instead of written dialogue. But the richness of the first-hand stories gave them enough material, and they were also able to insert themselves into the story from beginning to end.

At one point they exchange about both having always thought that “Tashme” was a Japanese word. In fact, in a cruel twist, it is an acronym of the first two letters of the names of the three British Columbia security officers responsible for its creation: Austin TAylor, a prominent Vancouver businessman, John SHirras of the BC Provincial Police, and Frederick John MEad of the RCMP. TASHME, the largest internment camp to grace yet another incident in Canada’s racist “past.”

It wasn’t until 1949, four years after the war was over, that Japanese Canadians were finally given back full citizenship rights, including the right to vote and the right to return to the west coast.

The creators of this play wanted to keep this history alive for descendants of survivors of internment and its legacy. As they say themselves in the program: “As a general rule, stories of internment have not been passed down and remain largely untold in Japanese Canadian families..when we sat down in formal interview with our elders, we were asking for and hearing these stories for the first time…the murky picture of our families’ past – our legacy – was finally being fleshed out.”

But in fact they keep it alive for others who really need not to forget about Canada’s racist legacy. The week I saw this play was a bad week: the week of Trudeau’s blackface and brownface disgrace. We don’t need a legacy of apologies, we need justice.

In the play, a Nisei who was interned at Tashme at 10 years old gets a monologue about having to burn all her toys before being forced to leave her home and says: “I remember that one of our neighbours was German, and I remember thinking, why doesn’t he have to leave? “

The Tashme Project was a part of the Prismatic Arts Festival, founded exclusively for artists of colour and Indigenous artists, first based in Halifax and now beyond: check out their future lineup here

The Tashme Project closed out the Prismatic Festival ending with a performance of Ottawa’s Oto-Wa Taiko drummers. In the drumming company was a Nisei who was interned for 4 years, partly in Tashme. His brother didn’t survive, was drowned at 3 in the Tashme river and is mentioned in the play as one of a number of children who met that fate while interned.

The power of this play (and of the whole Prismatic festival) in giving direct voice to survivors of the racism of the Canadian state is yet another reminder that both racialized settlers of Canada and Indigenous people have an essential artistic and political voice that needs to be heard, and so much is still unheard.

The loudness of the apology cannot muffle the silenced voice of what actually happened.

But allies should hear this voice, and challenge the Canadian white-washing of history. What happened at Tashme and the other internet camps is unfortunately still with us.

Section: