Features

You are here

Ideas and experience: how I became a socialist

August 12, 2020

Like many comrades, for me it all started with reading. Reading and experience.

As someone who grew up in the 60s you would think that should have been the epitome of the best capitalism had to offer. But North American capitalism was coming to the end of the longest boom in its history, fuelled strangely by the Cold War and military competition between the world’s two capitalist superpowers–the US, representing free market capitalism and the USSR, socialist in name only, bending all its resources not to the needs of its citizens, but to competing on the international stage to see which of them could potentially kill off the world’s population more times than the other.

For the working class in North America and for my own family, the experience of living in a system that purported to be the best of all possible worlds didn’t seem to correspond to our lived daily experience. My Dad spent the last 14 years of his working life working two full-time jobs in order to support his family of six and as a result only survived a couple of years after his retirement.

As for my Mom, her life was circumscribed by the expected reality for women of her generation and her class–raising six kids with limited means and feeling ashamed of not being able to provide for her family what were seen to be the accoutrements of middle class existence.

The sixties was a period when it was anathema to admit that you were working class. It was much preferable to call yourself ‘lower middle-class’ or one of the other multiple gradations of class much favoured by sociologists of the time.

When I read Saskatchewan Metis and activist Howard Adam’s Prison of GrassI could identify with his description of his father and grandfather as the ‘defeated generations’. Not, of course, that my family’s experience was the same or even came close to that of Indigenous and Metis people in western Canada, but I could identify with that feeling of being ashamed of one’s background and also feeling powerless to change the situation.

When I later came across Marx’s formulation of the need for the working class to move from being ‘a class in itself to a class for itself’ in order to make revolution, it made perfect sense to me.

American feminist and socialist writer Marge Piercy (who grew up in a working class family in Detroit) talks about the gifts she received from her family without even realizing at the time what gifts they were. I could say the same about the weekly trips to the local public library when my mother would pile us all in our second-hand car and we would leave with armloads of treasures to be devoured that week. I started by reading what my mother was reading, the mystery novels of Agatha Christine and others, but this opened the door to much broader worlds.

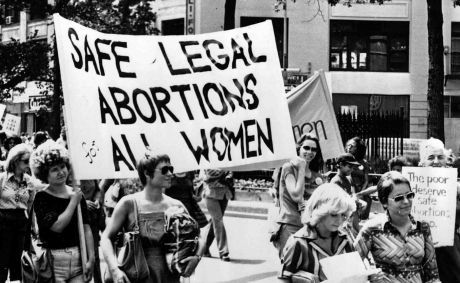

I would later read the novels of Steinbeck, Theodore Dreiser, Thomas Hardy, Dickens and be introduced to the injustices of the system, as well as to the sexism that was a part and parcel of the world as we knew it. Reading Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuchin high school my mind was blown open by coming face to face with the reality of women’s oppression which I could see in practice every day and all around me.

Reading also introduced me to the reality and horrors of racism. The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, Native Son by Richard Wright, the work of James Baldwin, the novels of Ann Petry, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison and more were a searing indictment of capitalism as a system awash and founded on the blood of African-Americans, brought to the continent as slaves.

But it was only really when I encountered socialists and the ideas of Marx, Engels and other revolutionary writers that I could see a way of joining experience with action and trying to affect change in a world that seemed to be always pushing us down, whether ‘us’ was defined as women, Indigenous people, Blacks and other people of colour, or more broadly as the whole working class, which encompassed all of us together.

Through many struggles and most particularly in my case, in the anti-war movement that sprung up around the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9-11, and from becoming a member of the International Socialists (which I joined upon moving to Toronto in 1987), I have learned that to really fight for change we have to do this together.

I have never regretted becoming a member of the International Socialists because, whatever faults and shortcomings we have, and whatever mistakes we have made over the years, the organization and the larger international tendency we are a part of, remain committed to the fight against oppression, the fight for a better world and the fight for the world working class to finally become that class for itself that Marx wrote about and did his utmost to bring about, both through his writing and his activity.

Today new generations are learning these lessons in the heroic struggles that have sprung up in Black Lives Matter, Idle no More, the environmental movement. I think it is critical that these struggles incorporate Rosa Luxemburg’s insight that in order to end capitalism, before it ends us all, we must ground our struggles in the working class, since it is this class which is the basis of all wealth creation for the capitalists, who continue to oppress and exploit us all in their search for profits: “Where the chains of capitalism are forged, there they must be broken. Only that is socialism, and only thus can socialism be created.”

Section: