Arts

You are here

Which side are you on?

May 15, 2012

From Victoria to Vladivostok, by Benjamin Isitt

Reviewed by Jesse McLaren

“Influenced by labour agitation, their morale weakened by poor weather and the Spanish flu, two companies of Québécois conscripts refused to leave Victoria for Vladivostok, and the military authorities used force—revolvers, canvas belts, and bayonets—to ensure their deployment to Russia.”

The little-known mutiny of December 21, 1918, served as the focus for Victoria-based historian Benjamin Isitt’s important, and well-documented, recent book. (For an accompanying online resource, visit www.siberianexpedition.ca).

The Russian and German revolutions had put an end to the barbarism of WWI, but Canada joined a dozen other nations to invade Russia—with Canada sending 4200 troops. Through the war Russia became the 7th largest market for Canadian goods—including submarines, rifles, ammunition, saddles, and railroad cars—and Canadian corporations were keen to see their profits of war continue. Meanwhile, Canadian elites were increasingly anxious about growing labour unrest, and hoped that crushing the Russian revolution would eradicate radicalism at home.

Quoting working-class papers of the day, Isitt documents growing labour militancy, which identified with the Russian Revolution. Socialists like Ginger Goodwin organized rank-and-file resistance, with strikes shutting down the production of munitions on which the war industry depended. The killing of Goodwin triggered a general strike in Vancouver on August 2, 1918, the first city-wide general strike in Canadian history.

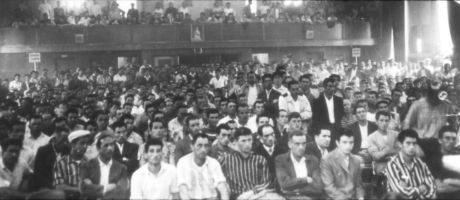

Meanwhile socialists in Victoria invited hundreds of Quebec soldiers to mass meetings against the Siberian expedition: “at this junction of social forces—the converging interests of working-class Quebecois and BC socialists—a violent standoff erupted in Victoria.”

The troops were eventually forced onto the ship, and Isitt traveled to Vladivostok to document the revolution they were sent to suppress. Vladivostok was an important transit point for western war materials flowing into Russia, and gold to repay loans flowing out. As Isitt recounts: “under the leadership of Sukhanov, the 24 year-old student, and three young Bolshevik women, the Soviet set out to democratize Vladivostok industry. Workers’ committees ramped up production of railway rolling stock and retooled the city’s Military Port to build and refurbish civilian ships and machines. Working-class housing was built closer to industry in order to increase workers’ leisure time, and the Soviet opened a people’s university, three theatres, and two daily newspapers.”

Foreign intervention overthrew the democratic Soviet, and Canadian troops occupied the local cultural theatre. Inter-imperial rivalry, the brutality of the White armies, and the resistance led by the Bolsheviks—including strikes along the Trans-Siberian railway—eventually drove out the invading armies, but the revolution was isolated and capitalism re-emerged.

In Canada, the Siberian expedition backfired, with labour councils across the country demanding “Hands off Russia” and endorsing the Russian Revolution. It was in this context that the Winnipeg general strike of 1919 erupted. But the same powers that sent troops against the Russian Revolution also suppressed their own people. Isitt shows how Canadian working-class and socialist organizations and their newspapers were banned—as were texts from Lenin and any public meeting conducted in Russian—and the Winnipeg general strike was violently repressed.

This book makes clear the importance of the Russian Revolution, the possibility of global social transformation, and the role of socialists: to build international, working-class resistance against capitalism and war.

Section:

- Log in to post comments