News

You are here

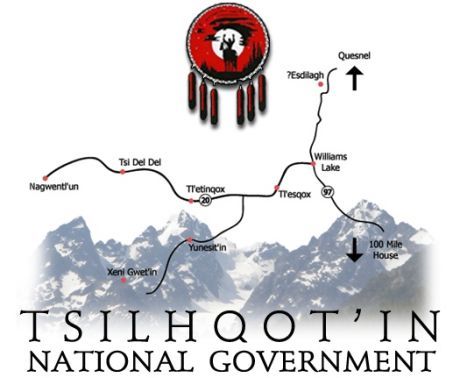

Victory for Tsilhqot’in and all First Nations

June 27, 2014

After over 150 years of struggle for self-determination, plus action in the courts for the last 20 years, the Tsilhqot’in First Nation claimed victory in a June 27 Supreme Court of Canada decision.

The Nation appealed to the SCC to overturn a BC Court of Appeal ruling, which had narrowly defined “aboriginal title.” The SCC decision gives First Nations “the exclusive right to decide how the land is used, and the right to benefit from those uses.” Provincial or federal governments that want to undertake economic activity without the consent of the First Nation holding title must prove “compelling and substantial public interest.”

Background

The court action began when Tsilhqot’in sued the BC government for allowing logging operations on traditional territory without consulting the Nation (let alone obtaining consent), stating that this breached the Nation’s title to the land. At the crux of the court hearings was how to define Aboriginal title.

The BC Court of Appeal more or less decided that Tsilhqot’in had title only to those small areas where it could prove historic use: the rock one stood on to go fishing, the hunting grounds, the winter villages. The Tsilhqot’in argued, quite logically, and as agreed to by the BC Supreme Court and now the SCC, that they could not access those use spots without traversing the land and water in between and that title should, therefore, extend to the entire area, 1,750 square kilometres.

The importance of the decision

The decision is important for a number of reasons. First of all it will give confidence to other First Nations to continue declaring their rights, whether through litigation, negotiations, or assertion. And, as Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief of BC, Jody Wilson-Raybould said, “This decision… will be a game-changer in terms of the landscape in BC and throughout the rest of the country where there is unextinguished aboriginal title.”

Secondly, this is the first time there has been clarity that those who want to use the resources on territory held by aboriginal title must not only consult with the First Nation holding title (which is the current requirement) but must obtain consent. This is a huge step forward.

Thirdly, provincial and federal governments have wanted to limit “title” to traditional uses, like hunting and fishing. The SCC decision reaffirmed its 1997 decision and opens the use of the territory to additional uses as these are identified now and in the future.

Reaction from First Nations

The immediate response from Tsilhqot’in and other First Nations was ecstatic. As Tsilhqot’in Chief Bernie Elkins said, “on title lands we’re going to have a veto. The days of easy infringement are gone.” Grand Chief Steward Phillip of the BC Union of Indian Chiefs echoed the sentiment: “We’re moving away from the world of mere consultation into a world of consent. And that is absolutely enormous when one considers Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline proposal… and a whole multitude of major resource projects.”

And Peter Lantin, president of the Council of the Haida Nation, one of many concerned about spills by oil tankers noted: “The entire script has been flipped today in regards to what is in the national interest.”

Reaction from BC and federal government

One can only imagine the disgust that the Tories have for the SCC increasing tenfold. Federal Minister Bernard Valcourt stated “the best way to resolve outstanding aboriginal rights and title claims is through negotiated settlements that balance the interests of all Canadians”. These are code words for “let’s stick with the treaty process because that allows us (government) to stall and obfuscate forever, all the while allowing our corporate buddies to log, mine, fish and pipeline their way through First Nations lands.” And the reference to “all Canadians” should make us all cringe, when what is referred to is the dismissal of “minority” rights.

The BC Minister of Justice, Suzanne Anton, stated in a similar vein that “BC is committed to continue to work together to make sure we all have healthy, thriving communities both socially and economically.” And how is that working out so far for BC’s First Nations? Obviously, not so well or there would not be so few signed treaties, such huge protests against proposed pipelines, and the Tsilhqot’in litigation, which one can only assume will soon be replicated by other First Nations.

Silence from the business community

It is striking how little has been said, at least in public, by resource companies who have been making it rich off indigenous lands for years, and who planned to keep on doing so. One member of the Petroleum Association interviewed by CBC, trying to appear perky, noted that at least the decision will bring certainty and emphasizes the need for engaging Indigenous peoples. But mostly all one can hear, if listening closely, is the gnashing of corporate teeth.

What to watch for

As we have written earlier, the use of litigation is one of three strategies typically used by indigenous peoples to declare their rights. The other two are negotiation (e.g. treaties) and assertion (blockades, direct action). The SCC decision will be of great assistance in negotiations, especially in BC, which is largely unceded territory. But it will also assist First Nations’ arguments made in other parts of Canada and Quebec where treaties were vaguely defined or never honoured properly. So watch for a lot more court cases going forward, by those First Nations that can afford the legal fees.

But direct action will likely remain as a strategy, given the tendency of federal and provincial governments to support private sector resource extraction, all in the name of the public interest (all those “jobs” you know… a cover for maximizing short-term profits regardless of environmental or social costs). And corporations wanting to further exploit Alberta’s tar sands will use whatever means they have to push their agenda, and will place enormous pressure on “their” members in the provincial and federal legislatures.

That is why we must continue to actively support the assertions of Indigenous peoples to control their resources, a key component of self-determination.

Section: